“I didn’t want to do something that was sad and show death or anything, but I wanted something that was not for white tears,” said New Mexico State University studio art major, Citlali Delgado, about her most recent artwork, “Ni Una Mas.”

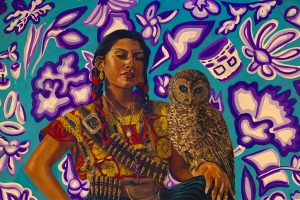

Concluding her college career with an unforgettable legacy, Delgado hung her first large oil painting in Garcia Center at a ceremony on Tuesday, April 22. This seven-foot-tall painting depicts a modern Chicana woman in traditional dress.

Before being displayed in Garcia Center, this painting stood in the Museum of the Big Bend in Alpine, Texas for their showcase, “Ecos del Sol: Portraits of Mexican American Heritage and Culture.” For about four months, this exhibit showcased various artists recognizing many cultures.

This art piece is layered with various symbols of heritage, from the background displaying Oaxaca patchwork to details of flowers native to Mexico embellishing the bottom of the canvas. Centered is the Chicana woman, wearing a huipil with bullets draped over her chest.

Delgado said this painting is inspired by her friend, Karla Robles-Guzman, president of the NMSU Latin American Student Council. When the inspiration arose, Delgado and Robles-Guzman went to the park with only a stool and an idea, where they came up with the empowering pose displayed in the painting. For this painting, Delgado was not only moved by the tragedies of femicides occurring in Mexico, but also the story Robles-Guzman had to tell about her own family.

“I was doing research on the femicides in Mexico at the time last year, and Latin American Programs were hosting events on that topic,” Delgado shared. “And they were, you know, hosting poster making workshops for International Women’s Day when the protests happened, and then they did a screening of a documentary on the femicides, specifically in Juarez. And, so, that’s when it like, it gave me a light bulb.”

She mentioned she wanted this painting to represent prosperity and hope – not to bring sadness or pity, but to show that Chicanas are strong, immovable figures. Aside from the traditional dress the woman in the painting is wearing, Delgado added small details to indicate to the audience that this is a modern woman, like acrylic nails and layered necklaces.

“This painting has been known to be like the modern agenda. I didn’t want it to be something that was just thought of as in the past. You know, all of this is like, continued, and we’re living in the consequences of, you know, these patriarchal society systems,” Delgado said. “And so, I wanted to show this is who she is, even though she’s, like, dressed up – but this isn’t a costume either. Like, this is her actual life. And so, the nails come with it. She’s fierce, and, you know, don’t mess with her.”

This strong figure, modeled and inspired by Robles-Guzman, is embedded with the story Robles-Guzman shared about her life in Oaxaca, Mexico with her grandmother. She described how welcoming and caring her grandmother was as she grew up.

“I am from Oaxaca, Mexico, which is a very indigenous state in the country,” Robles-Guzman shared. “And Citlali found me wanting to make this painting during a time where I was really unearthing a lot of the stories about my grandmothers and just my female ancestors, specifically the gendered violence that they suffered throughout their lifetimes.”

While Robles-Guzman was growing up, her grandmother worked as a midwife. She learned that her grandmother was in a forced marriage, was only allowed to go to school up until the third grade, and never learned how to read or write. But after she fled her arranged marriage with Robles-Guzman’s grandfather, life began to shine for her grandmother.

“I also wanted to honor the other female ancestors that I didn’t get to meet on my mother’s side,” Robles-Guzman said. “They’re from up north in the state, but my great-grandmother, she was a single mother, and she was able to get by, by weaving baskets and selling them. So that is a very big part of my family’s history, as well – many women who were in forced marriages, who suffered from sexual assault, who had to raise children by themselves, but that were able to do so with so much wisdom and knowledge and that were also so tender and so loving to us.”

Delgado and Robles-Guzman created this artwork to transform the suffering of Chicana woman into powerful figures, signifying change and determination. The two threaded their own history and the history of Chicanas everywhere through this painting.

“So many times, we look at our family’s history and we see pain,” Robles-Guzman shared. “But even in that pain, we can see how the people that came before us were able to turn that into joy and abundance and so much unconditional love for all of us, and that is the reason why we’re here.”