This story contains content related to sexual misconduct, which may be distressing to some readers. If you or someone you know is struggling, you can call La Piñon at 575-526-3437. The Office of Institutional Equity also provides resources at https://equity.nmsu.edu or 575-646-3635.

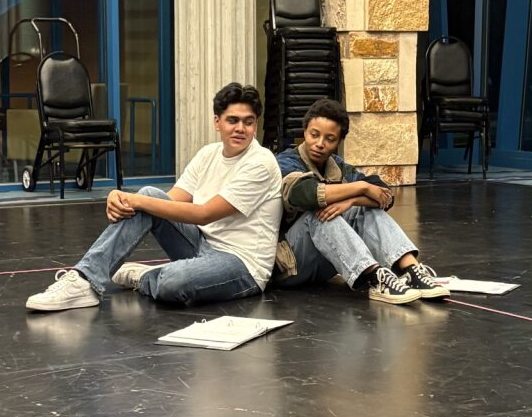

Prospects of a mandatory consent training course arose after a New Mexico State University student filed a lawsuit in 2022, reporting being raped by fellow student Aizen Robert Saucedo. After she initially filed a rape report, she accused the university of failing to protect her by prolonging the investigation and allowing her alleged rapist to attend classes. In July 2025, a $1 million settlement was made where NMSU agreed to implement consent training courses, though I question how effective those will be.

While the exact details on what the consent course consists of are still being worked out, Aisha Gutierrez, Interim Director of the Office of Institutional Equity (OIE), gave some insight into the goals of the course and what the material will entail.

“What does it look like to be a healthy participant, right?” said Gutierrez. “Am I asking for consent? Am I respecting the other person and their boundaries, right? That’s where we have, I think, the disconnect is making sure that everyone is well informed.”

Training may come in the form of an hour-long online course following the rules set by Title IX, Gutierrez said. The course would cover a variety of topics including what constitutes as sexual assault, what consent looks like, and how to report instances of sexual assault. Failure to complete the course will result in a registration hold.

Consent training courses are far from a new concept; in fact, NMSU seems late to the game. The 2010s saw a rise in them after sexual violence became labeled as a form of sex discrimination under Title IX.

Despite the increase in the number of universities offering consent training, there is little evidence of its efficiency in reducing sexual misconduct. A study done by the journal, Violence Against Women, attempted to evaluate this in 2022, finding there was not enough evidence to draw a correlation between courses and reports.

Though, if consent courses had a positive effect in lowering sexual assault, you would at least see a pattern of better behavior.

I investigated the crime trends of Northwestern University Evanston campus, which started to require consent training in 2015, and Stanford University, which began in 2016. Despite both requiring consent courses for a comparable time, they show different trends of sexual assault. When evaluating the data, I excluded the year 2020 because the Covid pandemic rendered the training inapplicable.

In 2014, Northwestern had three rapes recorded on the Evanston campus, which increased to eight the following year, according to their annual safety reports. Rape reports continued to increase from eight in 2015 to 13 in 2016, after the university administered the consent courses. In the following years, the campus saw a general decrease in reported rapes, with three reported in 2023.

I do want to note that there is no substantial evidence the training at Northwestern University is the cause of this decrease. However, Northwestern University has not avoided lawsuits for sexual assault during hazing in 2024— something NMSU is not foreign to.

Stanford, on the other hand, has maintained a consistent upward trend in rapes each year. In 2015, the year Stanford implemented consent courses, Stanford had 25 rape reports. Then in 2016, the number of reports increased to 33. Up to 2023, the most recent report, the number of rapes reported stagnated to between 30 to 33 reports per year.

Within the parameters of only two universities, their variables show that there is no correlation between the consent courses and a decrease in rape reports.

The consent courses are not inherently negative; however, deciding to only implement training after a lawsuit shows the lack of empathy that NMSU has for its victims. This feels like the university’s way of slapping a Band-Aid over a bullet hole.

Elicia Montoya, the victim’s attorney, pointed out that the lawsuit is indicative of the university’s failure to support the victim after she reported her rape. What I would have preferred to see is NMSU evaluating where it went wrong after the victim filed her rape report and detailing a plan to restructure their system to better protect victims.

Abel Friedman • Aug 26, 2025 at 9:16 PM

Real accountability begins with money. Maybe the university could recoup the costs of the settlement and the cost of the legal defense of the guilty parties (dear Title 9 office, you are guilty as sin) from the guilty parties. As long as you charge the taxpayer matters will never improve.